How is she bridging the Japanese and UK theatre scenes?

The British theatre director and producer Alexandra Rutter adapted Hayao Miyazaki’s world-famous “Princess Mononoke” anime in 2013. Her play, based on the 1997 masterpiece by one of Japan’s most distinctive anime creators, was successfully staged in both London and Tokyo.

That experience of working in Japan in 2013 left Rutter keen to return here to work with Japanese artists. In 2016, an opportunity arose to do that when she got a scholarship from the London-based Daiwa Anglo-Japanese Foundation to study Japanese, and took up a work placement during its 19-month programme.

Then, some 10 years after her production of “Princess Mononoke,” and after becoming a Japan resident, Rutter chose to give “The Garden of Words” (“Koto no Ha no Niwa”) — a 2013 short film by the prominent Japanese anime filmmaker Makoto Shinkai — its first-ever theatrical adaptation in a version created by herself with Susan Momoko Hingley.

So in August 2023, Rutter got back to London to present an English-language “The Garden of Words” — based on both Shinkai’s anime and a novel he wrote about it — with auditioned British actors in a month-long run at the Park Theatre in north London. After that, she returned to Tokyo to re-work the production for the much bigger Stella Ball theatre in the city’s prestigious Shinagawa Prince Hotel.

As she was in the midst of those preparations, Jstages.com caught up with Rutter to ask her about her Anglo-Japanese production; what is uppermost in her mind creating plays for each country; and what she believes are her unique strong points in making theatre based on anime, manga and/or videogame sources.

How did you find it creating “The Garden of Words” for London?

As it was such a long time since I’d worked on a production in Britain, I really really enjoyed it. It was a very different process from what happened here in Japan so I had to get used to different ways of working.

Most of the actors I worked with were of Japanese heritage, so we had Japanese and English speakers in the cast and also British East Asians. So that was a real privilege for me, I was able to work with artists like that and be able to run the audition process by myself and choose all the actors. It was a reverse culture shock for me.

Stage photo of the UK production in August 2023

Just after you staged “Princess Mononoke,” you said in an interview that you wanted to dramatize “The Garden of Words” in the future. Why did you want to do that?

There were two big reasons. One was because I was just really moved by the film; I found it’s true to life and upsetting and very cathartic in an interesting way.

Secondly, I went to see it at a film festival and I was just blown away that you could choose anime as a form of expression for this type of story. So, my incorrect assumption had been that anime was more like fantasy, or science fiction, and I think lots of people in the West also had that image.

However, when I saw the film “The Garden of Words,” it was a very everyday story that I thought was challenging a stereotype of anime, and I was fascinated by anything that questioned the status quo.

So when I saw it I thought it would be great to bring it to the stage, both because that would challenge expectations of what anime is, and also because the content was suitable for the stage.

In the West, we tend to think that anime is a genre rather than a medium, so that was something I wanted to challenge by staging this work.

From the beginning, did you plan to do it in both countries, the UK and Japan?

Ever since “Mononoke,” I’ve wanted to make work in both countries and introduce Japanese artists to the UK and British artists to Japan and have a real Anglo-Japanese collaboration. That was something I was really interested in. So, I think that from very early on, the idea was always there.

For instance, I hoped we could swap cast members, with some ensemble members from Japan coming to England, even if they didn’t speak the language, and vice versa.

It’s like sister shows. I try to cross over some of the departments, like with the projection designer and print designer from London and the puppet designer is coming to Tokyo. So we have got some crossover, but of course it’s very expensive to do it with everybody.

I know how much the actors we work with in Japan wish they could perform in England, but because of the language barrier it’s not accessible for most people, though with work that’s heavily movement based, for example, I don’t see why if I speak enough Japanese to communicate with actors here, then I couldn’t take Japanese actors to the UK.

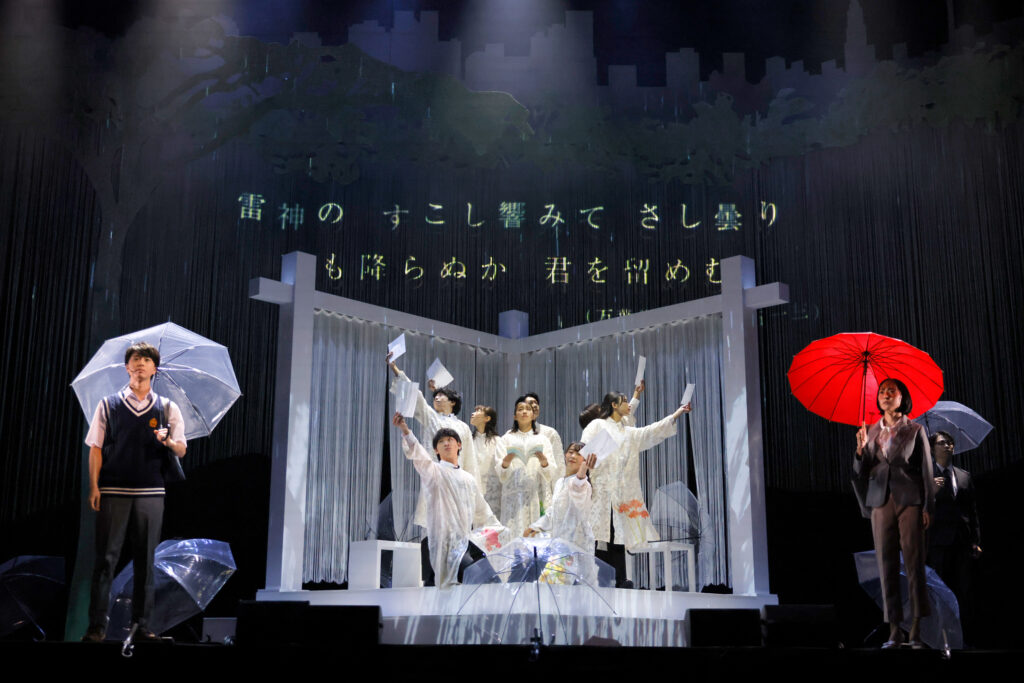

Stage photo of the Japanese production in November 2023

How did you make the adaptation for theatre from the combination of two sources of Shinkai’s anime and his novel?

The adaptation basically follows exactly the same arc as the anime, so the whole 46 minutes you see in the anime, you will see on the stage.

Meanwhile, the book essentially explores the back stories of a lot of the characters and why some of the mainly minor characters behave the way they do in the anime, which I find fascinating as a fan of the film. So it was a process of trying to bring together those very different styles of storytelling, along with reflecting the highly beautiful visuals of the film in a way that’s very theatrical.

It’s very challenging to bring all of those different things together, but also quite confusing with the slightly different tones.

But actually, the biggest thing was perhaps constructing something for London audiences, but then taking it to Tokyo where the audiences know the original so much better.

In London we could be much more vague with a lot of the smaller details, but in Tokyo people are more aware of these things.

Overall I think it’s very faithful to Shinkai’s source material, but in order to make it work on stage it has quite a lot of adaptation as well. So I hope it feels fresh through the lens that myself and my co-writer, Susan Momoko Hingley, have created, but equally that it represents the anime.

The Tokyo version is very closely based on the London staging, but we did alter things like some of the time-line which we invented. So the structure is a little bit different though the base material is pretty much aligned with the London version.

But because we were coming back to the work’s original language, a lot of the dialogue has returned to its original form, whereas in London the translations to English didn’t always work so well for the stage so we changed quite a lot of small details.

Are there any other significant differences between the UK and Japanese versions?

The cast size is dramatically different. We had a cast of seven in London and we have 15 in Tokyo, so it’s more than double. Here, too, we have a chorus of poets who deliver the poems as well as physically construct the world in which the characters live — so there is a big chorus movement, which is how I tend to work. In London, though, the chorus also played the characters, so physically speaking the English cast was a lot busier doing everything.

If anyone has seen both shows, they will have very much seen two sides of the same coin, though detail-wise, there are quite a few adjustments to make it work for a Japanese audience.

My job I think as a director and a writer on this project — and also my responsibility I suppose as a person who has lived in Japan and who has tried to learn the language — is to consider what I need to change to make it be understood in the way that was intended. Sometimes you have to change quite a lot, and vice versa. So what do I have to keep in for the Japanese audience to feel it reflects a work from Japan, but equally is fresh enough in terms of its new approach to the staging, direction and writing and everything else.

I like to make my life difficult (laugh). It’s complicated, but it’s brilliant. I am very pleased that I’ve chosen to put in that effort to make it different. And all the team in London and Tokyo are working so hard to get the right balance. So it’s really, really exciting.

Stage photo of the Japanese production in November 2023, a chorus of poets

How about the theatre size in London? What capacity was it?

The Park Theatre in Finsbury Park in London was 200 seats and it was a beautiful, intimate space with a balcony. That was a great place for this show, but it’s a different challenge to put it on a stage this big at the 876-seat Shinagawa Prince Hotel Stella Ball.

It’s more challenging here than in London, because I try to make it very intimate, so even a two-person dialogue fills a very big space. But it’s very different in terms of theatre for sure.

Though the music is the same by the same composer, Mark Choi, there are a few tracks that are new for Tokyo and the projection will be the same, by the same designer as in London, but there will be changes to make it fit better here.

The set, however, is a completely different designer. So, the puppet designer and the music and the writers, and the director, are the same, but the costumes are completely different, and lots of the set ideas came from me with the directorial concept, so it feels like there are a lot of similarities, but it’s a different designer.

A crow (as a puppet) appears as an important symbol in your production. What was your intention there?

The crow appears in the anime just once or twice, I think. I found the sequence of music and the crow flying around Shinjuku to be really uplifting. It made me think about the interesting binary of a crow being a quite dark and depressing image and having lots of connotations that are less than positive, but also a bird in flight being such an inspiring thing. So I saw the crow as being a metaphor for wanting to reach your potential, but not quite being able to, because it’s a balance between dreams and looking off into the distance and something that’s actually quite dark and even depressing at times.

Stage photo of the UK production in August 2023, a crow puppet

Stage photo of the Japanese production in November 2023, a crow puppet

English reviews of your work say you are one of the leading lights of the new generation in UK theatre. What do you think about the future of theatre?

I hope that the pandemic will have inspired us to be more creative and more daring with our choices for what we put on stage, and more keen to try new things.

When the pandemic hit us there were more online projects and different ways of showing things that were very exciting for someone who wants to share stories across cultures, so I’m hoping there will be more of that.

However, I don’t know if in reality people always tend to default to what they know, so I think that the old staples of particularly British theatre will continue. But at the moment there is a sort of trend of anime theatre in the UK and I think that will continue, which is very exciting.

Stage photo of the Japanese production in November 2023

Would you please tell me about the possibilities of 2.5D productions?

It depends how you classify 2.5D. Anime on stage, manga on stage, video games on stage … I think that’s really fertile ground for new creative thinking. I think whenever you take a source material that isn’t traditionally considered appropriate for the stage, it forces you to think differently and that’s a really fascinating and exciting and creative ground for anything.

I think anime, manga and gaming, yes, but 2.5D is also a genre of itself that is keeping very close to the original. So, I think they are like more faithful adaptations, and as for adapting anime for the stage I think it will be interesting to see whether people feel it’s a 2.5D show or not — although it’s of course an anime adaptation, so in that sense, Yes.

I think it’s because I feel anime, manga and Japanese pop culture is so accessible, and particularly to younger audiences, to open the gateway to Japanese culture in a broader sense. So the pop culture, anime and manga route is a really exciting way to do that.

Basically, then, our anime stage adaptation will be a bridge to other parts of Japanese culture, but I think by putting a source like anime on stage — which has not traditionally been seen as something that you do — it challenges what anime is as well as what theatre is.

So that for me is the most exciting thing whenever I have a conversation with theatres in London. It’s five years ago now, but the first thing they’d say is, “Um, anime is not really our thing …”

Then I think, what do you mean when you say anime? Is it what I used to think before I came to Japan, that it’s like SF or fantasy? But actually it is so much more than that.

It’s about creating diversity and challenging expectations of both theatre and anime. That’s what really excites me.

In London, as a theatregoer, but not an anime watcher, you would be surprised to find this story was an anime, and you might be interested to go and watch the anime. And vice versa, you might come to the theatre because you like the anime and you might find “theatre is actually quite fun, so I will go to see theatre. I never normally go to the theatre, but maybe theatre is for me.”

The way traditional theatre is in the UK, there is quite a barrier to entry as it’s expensive and you have to feel like you are a ‘theatre person.’ I think my interest is not in theatre that is for theatre people, but it is in inviting a completely different audience into the theatre. I think anime has the most amazing potential, and ever since “Princess Mononoke,” everything I’ve done in my work has been about expanding the audiences.

Stage photo of the Japanese production in November 2023