Toshiki Okada, who founded the globe-trotting Chelfitsch theatre company in 1997, and writes and directs all its productions, is one of Japan’s leading dramatists.

Throughout his career, Okada, 50, has always sought to reach audiences abroad as well as at home. Now, with his new play, “The Window of Spaceship In Between,” he aims to cross another boundary by staging it with auditioned non-native actors who may not be fluent in Japanese.

This follows several recent attempts by Okada to cross other borders in Japanese theatre, often by breaking down perceived boundaries between genres.

In 2017 he collaborated with a Thai writer, Uthis Haemamool, to create a play presented in both Thailand and Japan.

Then between 2016–2019 he created four plays with German and other European actors at the Muenchner Kammerspiele in Germany, while also presenting Noh and Kabuki plays in Japan and abroad with other contemporary theatre artists.

After that, in the summer of 2022 he staged a narrative dance program with the world-renowned France-based Japanese dancer/choreographer Ema Yuasa.

With each of these projects, Okada has consistently challenged accepted, often quite fixed, Japanese ideas about modern drama, just as he has proposed new possibilities for today’s contemporary theatre.

This time, Okada is asking audiences to reflect on their own expectations about “speaking Japanese on stage.”

When he worked in Germany, he says he witnessed several non-native actors taking leading roles due to their acting skills, even though their German was not fluent.

This made him wonder whether a similar thing could happen in Japanese theatre — which led him to start this project in 2021, believing it could work if non-native actors brought rich imaginations to their understanding of the script.

In September that year Okada held the first of four workshops for non-native actors, after which he had an open audition from which he chose four foreign actors* for this production.

So now, these four actors, together with two Japanese actors,** play the crew of the Spaceship In-Between in performances in Tokyo (finished) and Kyoto (Sept. 30–Oct. 3) at the Rhome Theatre Kyoto.

*

Qiucheng Xu /China; Tina Rosner/ Hungary; Ness Roque/ Philippines; Robert Zetzsche/Germany

**

Mari Ando; Yonekawa Your Leon

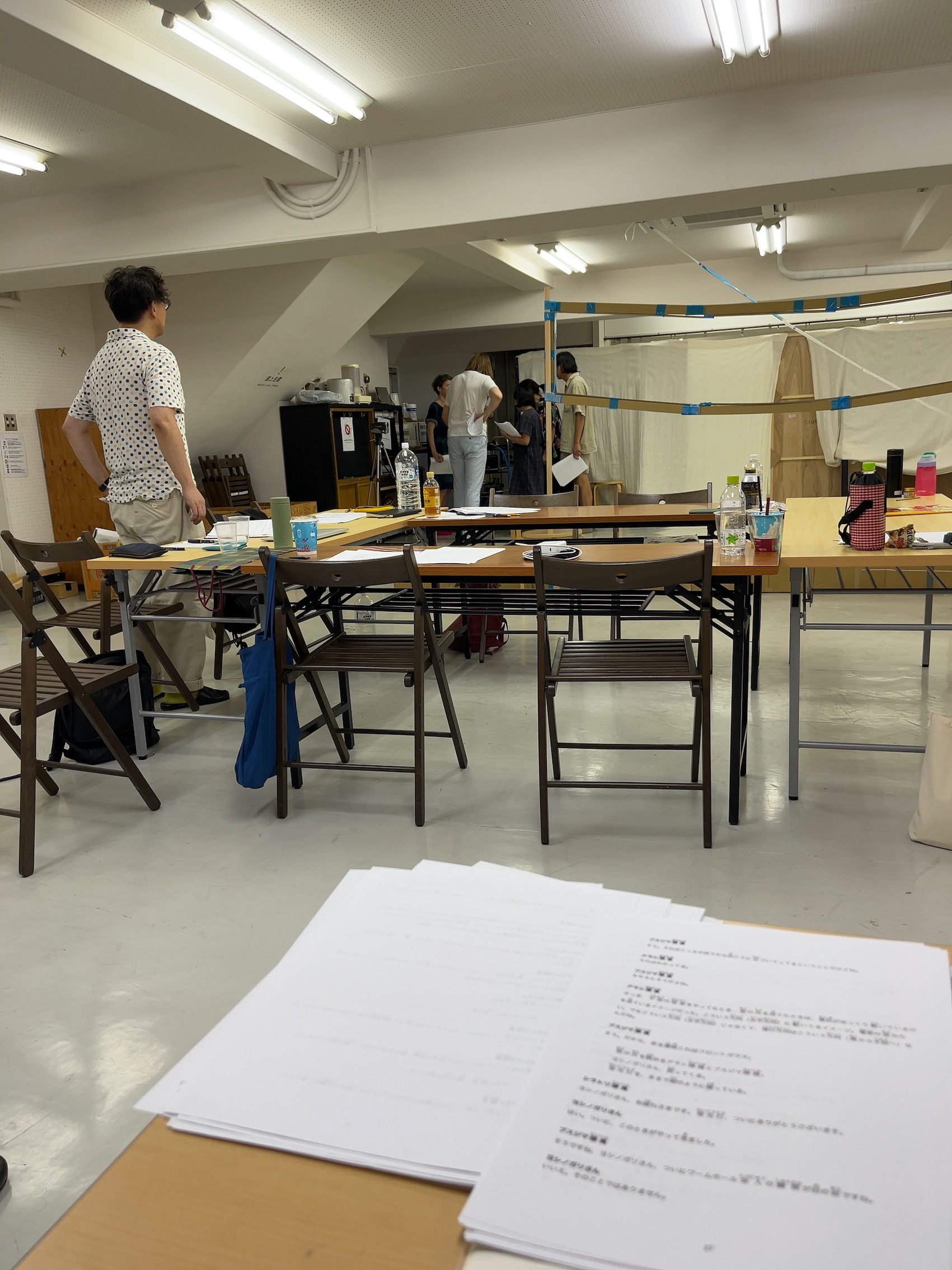

Before the opening night, Okada’s production company, Precog, invited the media to their rehearsal room in central Tokyo’s Waseda district, and when I got there the cast were sitting around a table in the middle of a script-reading session.

At once I realized that kana characters were written above all the kanji characters in the script, though both the non-Japanese and Japanese actors were carefully reading the lines in the same manner.

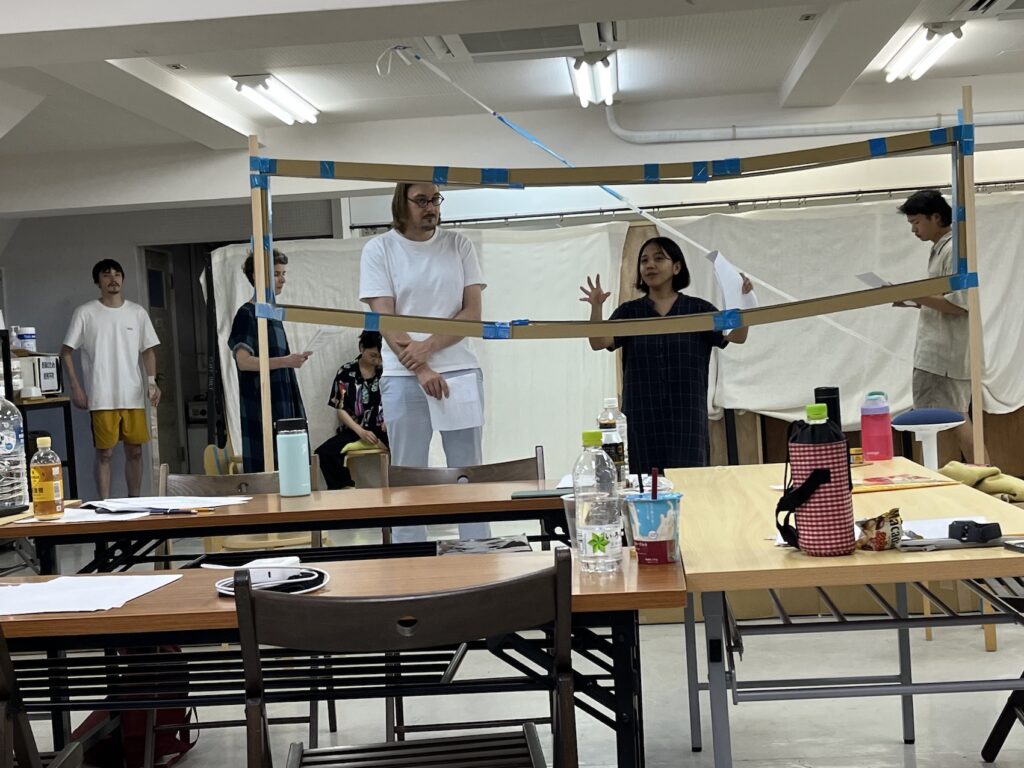

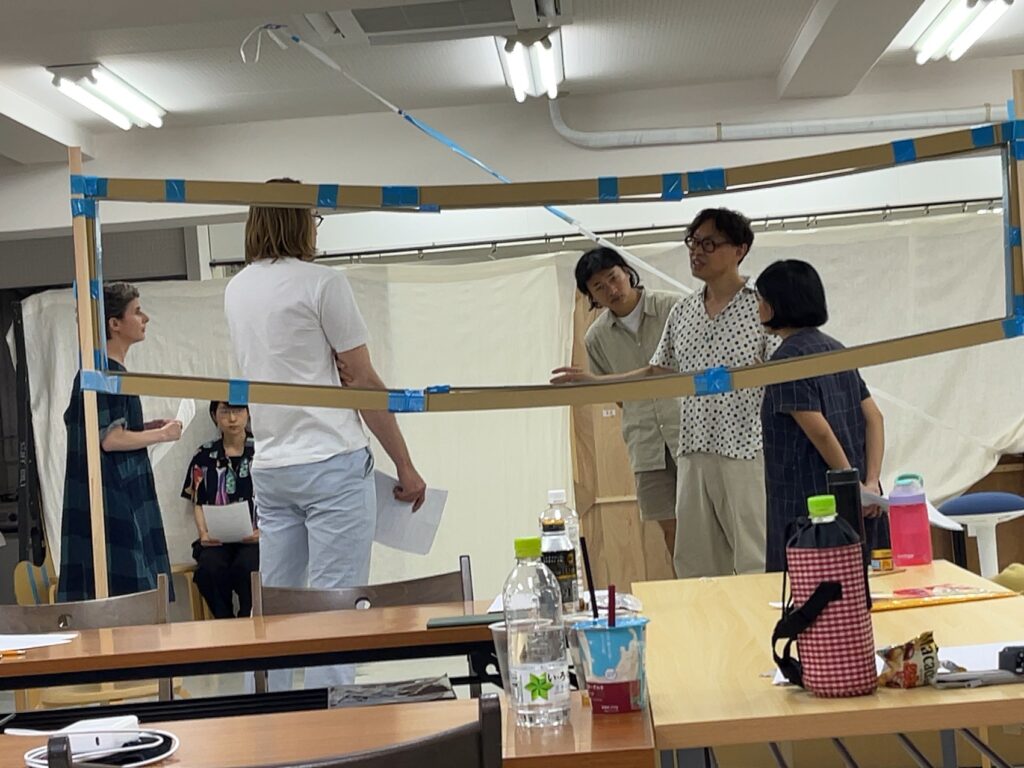

Then after a short break they started to rehearse the scenes with actions, with Okada explaining logically and politely why he chose his direction instructions — including his suggestions on Japanese-language intonation or phrasing — never saying anything like “because a native would say it like this,” or “this sounds more natural to Japanese.”

Consequently, there was always a clear reason why he asked the actors to say their lines in different ways.

One time, an actor stopped saying his lines and asked Okada to let him repeat them from the beginning. Then Okada immediately asked him why he felt uncomfortable, and discussed with him the verbal discrepancy he had felt in his own delivery.

“’The Window of Spaceship In Between” is a story that happens in a spaceship called In Between. The craft has four crews of different nationalities, an alien guest, and an AI robot — with the alien and the robot played by Japanese actors. As it is set far away from Earth, even though the narration is in Japanese all those aboard are equal citizens of Earth. Hence any privilege of being Japanese does not apply there.

Okada said, “When I started to write this play for this international project I thought it would not be effective if I set the story anywhere on Earth.

“I believe this is a project about the Japanese language. I’ve often felt that Japanese actors’ speech in the theatre was becoming a rigid and empty formality. Simply put, I sometimes felt their words were not getting to my ears naturally.

“I suppose there is a fixed idea among many native Japanese actors that they have a certain model way of speaking the lines in several situations and they just copy it. So they are simply satisfied with their natural intonations without being troubled by any doubt about the lines’ real meaning. However, that kind of apathetic speech won’t really get through to the audiences.”

In contrast, Okada believes non-native actors speaking Japanese don’t have such fixed ideas and, as they don’t have that empty formality in their speech, they read the lines with more sensitivity. As a result, their words will reach the audience naturally.

During the rehearsal, I noticed that Okada often urged the actors to “please remember the storytelling workshops.” So I asked him about those and he said he starts every rehearsal with that kind of workshop.

“At the beginning, a person talks about an episode that happened to him or her recently. Then another person, who was listening to the story, repeats that story in front of the others. We call this practice a ‘storytelling’ workshop. I believe that the relationship between the talker and the listener is very useful for acting practice, so I always remind the actors to use their imaginations in the same way they did in our storytelling workshops,” Okada explained.

Zhang Yiyi, who studies Intercultural performance at Tokyo University of the Arts, has written about this theatre project involving non-native Japanese speakers, including her own experience of taking Okada’s workshops. So, with permission, I am happy to draw on her research, as follows:

“The actors are required to tell the story through words in Japanese and physical expressions that are the product of their own imagination. At the same time, the listeners also use their imagination and try to understand the story. In this process, the talkers’ creative words used to tell the story and communicate with the listeners are more important than ‘correct’ Japanese by native speakers.

“(In this non-native project) everyone is a non-native Japanese speaker, so people try harder to imagine meanings and understand the others.”

Zhang continued, saying, “Non-native people’s Japanese speaking can stimulate the listeners’ thinking in such a way to realize a fundamental mission of theatre, which is getting others to think over again about themselves.”

Ultimately, as Zhang mentioned, I also felt this project was exploring more diverse possibilities of expression in theatre by appointing non-native actors who speak the lines infused with their colorful imaginations — as opposed to many native Japanese actors who speak their lines in formulaic ways without using their imagination.

“I hope audiences will reconsider the Japanese language when they see this play,” Okada said. “In a sense, that is the target of this project.

“I also hope this project will be a platform and there will be more opportunities for non-native people to perform on stage in Japanese theatre in the future.”

With such a renowned international dramatist as Okada regarding his new project as a great potential trigger point, there really is hope that this type of mixed-nations theatre is set to develop a lot more in Japan.

And I, for one, would like to believe that there are still huge unexplored possibilities in the future of this diversity theatre that Okada is now trying to open a path toward.

“The Window of Spaceship In Between” runs at the Rhome Theatre Kyoto as a program in Kyoto Experiment 2023 from Sept. 30–Oct. 3. For more details, call (03) 6285-1233 or visit https://chelfitsch.net/