The US playwright and actor Jeremy O. Harris appeared like a comet in 2018, dazzling the entertainment world at the 74th Tony awards when his second professional work, “Slave Play,” gained a record-breaking 12 nominations for a non-musical production, including for Best Play.

Coming after Harris’ low-key playwriting debut with “Xander Xyst, Dragon 1” at ANT Fest 2017 in New York, that three-act drama examining sexuality and racial trauma in the USA drew praise indeed from The New York Times’ chief theatre critic, Jesse Green, who dubbed it, “One of the best and most provocative new works to show up on Broadway in years.”

Yet beside his dazzling rise as a writer, this 6 ft 5 in (1.96 m) gay black man with big twinkly eyes has suddenly revealed other diverse talents as well, including as co-author on the screenplay of 2021’s film “Zola” directed by Janicza Bravo, and in ongoing projects with HBO and Netflix.

Beyond the worlds of stage and screen, this child of a military family that eventually settled in Martinsville, Virginia, is now also a model and influencer sought after by leading fashion brands including Gucci and Jean Paul Gaultier.

When I met 33-year-old Harris swathed in a kind of Afro-paisley Gucci jelaba for this exclusive interview in his luxury hotel room in Tokyo, he cheerfully explained, “I’ve just been in Paris for fashion week and I walked for Gaultier, and because of all the excitement of that I had a headache for a couple of days when I got here — but now I’m loving it. It’s amazing and Japanese people have been so kind.”

Using his break time between his runway appearances in Paris and shooting a TV drama there titled “Emily in Paris: Season 3,” the main purpose of Harris’ visit — his first ever to Japan — was to see his third professional play, “Daddy: A Melodrama,” which premiered in New York in 2019 and runs till July 27 at the Tokyo Globe theatre.

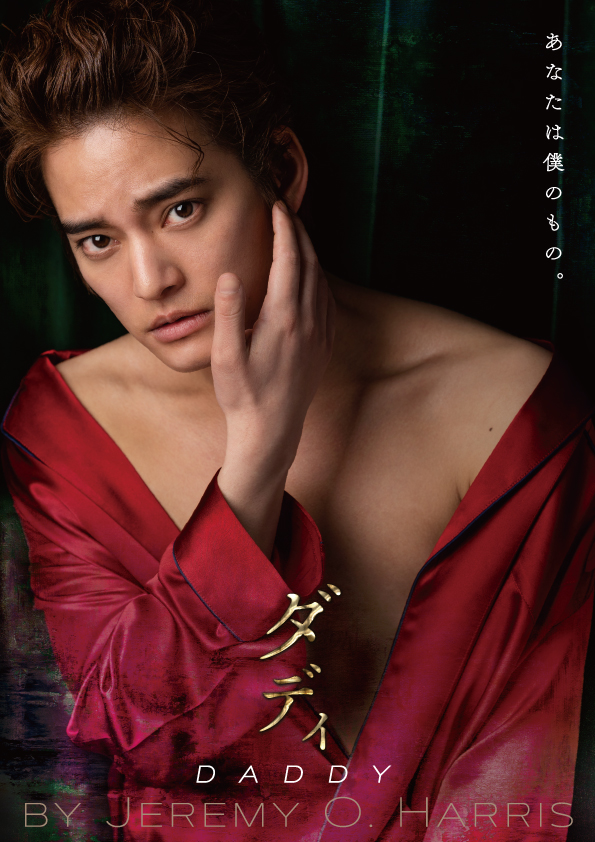

Harris’ first-ever production in this country, this is being staged by the New National Theatre’s artistic director, Eriko Ogawa, who studied theatre at the Actors Studio drama school in New York and is working with an all-Japanese cast featuring Yuma Nakayama from Johnny’s Entertainment in the central role.

A play with undoubted autobiographical echoes, ‘“Daddy: A Melodrama” depicts a promising young black artist named Franklin (played by Nakayama) as he wrestles with love and career and, of course, how it all relates to money.

When Franklin is invited to the house of a rich European art collector named Andre (Yasumasa Oba) after his first exhibition, the older man asks him to be his lover — and offers to be his financial patron … like a “daddy” figure.

However, after Franklin’s mother Zora (Misuzu Kanno) arrives and starts quoting the Bible to him, the tension in that human triangle heats up and eventually drives Franklin into a corner sandwiched between art and business that moves him to observe, philosophically: “Art loses its worth the minute it can be bought … it becomes worthless once it’s owned.”

What follows is almost the entirety of Jeremy O. Harris’ recent conversation with Jstages.com.

––––––––

Raising the curtain

I started on my way to being a playwright by loving acting. I did my first play in 5th grade. Around then I thought I was really good at it — and my teacher said I was really good at it.

Then I started reading a lot of plays and I became obsessed with plays.

But when I started working in the real world as an actor, I saw how limited work was — especially if you’re a young actor, a young boy and you’re 6’ 5”. You can’t really work as a kid and most people want you to play someone’s son but if you’re taller than everyone it doesn’t make sense for them.

So I started writing my own work so they would take me seriously. I was 18 then.

Writing for myself was how I first learned I was good at writing for other people. So I just kept on doing it.

Much more about writing

You know, acting is doing, and Shakespeare started out as an actor … and I think there’s something about knowing very deeply the stories you want to see; and knowing as an actor the stories you want to portray makes it very easy to write it down on the paper because you’re just imagining a situation you want to be in.

For example with “Daddy” I always wanted to be in a play where I was the center of attention … who had a psychic break like what happened to Miss Julie (in August Strindberg’s play of the same name) or like an ingenue in those great 19th-century plays, because usually when you’re a boy they expect you to be strong the entire play.

But I was like “No, I want to have a breakdown” … I want to be tender … I want to have a love scene.” So I wrote all that into a play.

There aren’t many plays like that, especially not about black boys, and not about gay boys either.

I wanted to create works like that or that felt like that inside of the canon, or akin to those works like “Miss Julie” or “A Doll’s House.”

But for me it felt very important.

Down but looking up

For the most part of my career as a young artist I didn’t have a real career. I was working doing very minor acting jobs.

I got my real career by writing a play for other people.

I was homeless basically before I wrote “Slave Play” … I was sleeping on friends’ couches; I couldn’t afford rent and I was doing all kinds of small jobs. But when I decided to focus on writing a play, I knew I couldn’t do that while doing all those small jobs.

About “Daddy”

I wrote “Daddy” in six months. I was dreaming of a future for myself on the page; thinking that one day I may be a famous artist. But hopefully I wouldn’t have to compromise my soul.

I wrote a play about what if I do compromise my soul; what will I lose; what will it take from me. And not to spoil it for anybody, but in the end of this play Franklin loses his mother and his friends and he’s left with nothing except the art he’s made, his play, and that’s sort of a tragedy and I didn’t want that for myself.

“Daddy” set me free and I got off the couch and it was my writing sample to get into graduate school at Yale School of Drama, and then again for the “Zola” movie that’s coming out to show the producers I could write a screenplay.

Refracting on Yale

At Yale I wrote “Slave Play” and that opened every door and I wrote that in the last year I was at grad school and I graduated a week after interviewing Rihanna for the cover of T magazine [The New York Times Style Magazine]. On the day of my graduation that cover came out and I found out my play was going to Broadway. Then I immediately left graduate school having started it homeless, but by then with an apartment in New York City and knowing I was going to have money for the rest of the year.

So, whereas I wrote “Daddy” before Yale, to get in, I think “Slave Play” has a lot of my Yale experience in it.

But in a lot of ways “Daddy” was like a metaphor of me going to Yale, because “Daddy” was like my Andre — and Yale was my like Daddy, though historically Yale was a white male-dominated school for a long time and women weren’t allowed to go there, and black people weren’t allowed to go there.

There’s a weird powerplay at Yale — how do I say this politely — Yale changed my life: They paid for me to learn how to be a playwright; it gave me access to all the education in the world; and some of the best art is at Yale, and some of the best artists.

But it also made me feel crazy often. Everybody who goes to Yale loses a bit of themselves inside of that program.

Yale’s school of drama isn’t interested in teaching you about being an artist; it’s interested in teaching you how to be in the business of making plays.

And for a lot of foreign students who go there that can make them feel less bad because, for instance, I had a good friend who, because she had an accent, the teacher said you won’t work in America; you need to get rid of this accent or you won’t work in America — which isn’t true in a macro sense, though it will be harder for her to get work consistently

But still, it was really destabilizing, dispiriting and disheartening sometimes to have that experience.

Art from experience

In all my work I’m trying to cut myself a bit and leave my blood on the page, because I want to leave some evidence of the life I’ve led and everyone who’s led me to the point of writing that play on the pages of that play.

What was really hard about “Daddy” was that to cut myself metaphorically I had to go to my dark childhood and not knowing my actual father, and that was something that for most of my childhood, and my adulthood even, I didn’t tell people.

I talked about my stepdad as if he were my dad and no-one knew that my actual father was someone who I’d only met one time in my life.

When I recognized that I was hiding that in the play, I had to open up that wound again. That’s where that scene in the dark with knocks on the door — that’s where that scene comes from.

So that was the hardest thing: Being honest with myself about something I’d been lying about my entire life.

I think that the marker of my work is that I’m not afraid to speak truths that other people find uncomfortable.

Freedom of expression through theatre

One of the things that theatre does specifically so well is put people in the same room with ideas. And not just ideas they can watch passively, but they’re active participants in those ideas because the people on stage can change the way they express an idea in a moment and that can change the way you feel about it and how the person next to you feels about it.

Theatre for me is a place that’s supposed to create dialogue and discourse. For most of the world, theatre — or even telling stories around a campfire — was brought to our villages in order to create some sort of change in the way people thought about the world around them.

Even in the Edo period here, the great kabuki dramas were there to change the way the populace thought about the projects of the emperor and the history of Japan. There’s a societal import to theatre that I think a play like “Daddy” can help to spark in people; to spark shifts in people.

Theatre business

I think it’s very important for people — especially in America — to think about capital, and capitalism, when they see a play, because theatre is a rarefied art form on wild class lines … and that’s not OK.

And any ticket to a play should never be $500, so hopefully when people walk out of a play like “Daddy” in America they’ll think about that.

I think in Japan this is a society in which art and commerce are very much entwined and you can’t get away from thinking about how so much of the history of this country has been distilled and marketed into these new objects of commodification that aren’t necessarily processed by the people who are buying them in America and Europe.

We have to start thinking about what that means for the artist who made it. What does it mean for me to toil over these beautiful narratives of this childhood trauma and have them go to America and just be seen as a cute story. What does that do for him?

I think that’s what “Daddy” is about: the artist, the art, and the money around all that; the stories that get told because of the money around all of that.

Japan’s take on “Daddy”

I’m in awe of the Japanese version of “Daddy.”

I said to some people that it’s the closest I’ve felt to feeling like Chekov or something, because when I, as a black American, am doing Chekov and I’m playing a landowner whose cherry orchard is being sold, I have no idea about it so I have to do all this research to make sense of it and then when I stand on the stage and do my monologue it has to feel real even though I’ve never been there.

And now, watching all these Japanese actors make sense of being a black, queer American in Los Angeles and doing it with such beautiful specificity that I’m seeing and that’s resounding with me, with my spirit and with my history, it feels so affirming that I’ve written it well.

And these actors have worked so hard and this director is so detailed — you know, she was able to render it so beautifully here in a language that’s so different from my own, but with actions and emotions that are so universal.

For a show like ours — you know, theatre already caters mainly to women — so many young girls are going to be there, maybe next to other people who may just know about American theatre and be excited about that, and the conversations they might have … you know, the person who’s excited about Jeremy Harris and seeing his work in Japan may not know about Johnny’s boys in the same way and they’ll be sitting in the lobby afterwards having a conversation and that’s so exciting.

Why “Daddy” names real people and brands

I think that in this play part of the importance of it is because Franklin, without realising it himself, slowly allows his art to become a commodity; he allows himself to become a brand, and everything around him is a brand.

The very first thing he says is that he doesn’t like things being sold, because when art is sold it loses its worth. That’s his big thing — and yet that’s what he allows to happen to himself throughout the play.

I think what he means by that is that when art is sold it becomes known for its selling price — it becomes a $1 million Basquiat or a Warhol or something — so I wanted to really hit that nail on the head and draw a relationship between that and a Tiffany’s bracelet or a “designer” T-shirt … because they’re all commodities … they all deal in capitalism, but just have different names.

Art and money and society (continued)

I think one of the things that’s difficult is that the individual cannot hold full responsibility for the issues of systems of power. So our governments have created societies that are completely linked, inextricably, to capitalism.

And as someone who is from a family that was destroyed by capitalism or who had very few resources because of capitalism … but as someone who has the potential to make a lot of capital … I have to walk that line as an artist because I have to provide for my family.

So walking that line has allowed me to support my mother and get her a home for the first time. That was my first big deal, but I also tried to create some socialist kickback where I would get money from HBO to help the New York Theatre Workshop, etc.

For me, the only responsibility I can hold inside a deeply fraught society is that I have to create undercommons or secret pockets for redistribution of wealth inside a capitalist system that’s trying to utilize my body and my labor.

About BLM

For me black life inherently matters, right, and all my work is inherently political because I’m thinking about politics all the time. And I’m thinking about history because I’m a Southerner, and I’m a black Southerner, so all those things are constantly woven into my work.

I don’t know that I ever need to write a work that’s about protesting or articulates that, because I actually think what is more discomfiting or more uncomfortable for people is a work like “Daddy” or a work like “Slave Play” that centers a black life, a black life that dramaturgically matters and it’s doing complex things and existing in complex ways.

Looking forward

I think the next thing I want to do is properly explore Tokyo (laughs).

Career-wise, though, I’m really enjoying producing and I’m enjoying supporting other artists a lot.

So I hope by the end of my career, people will look back at me and say not only was I a significant artist who produced works of great importance, but also that I took care of other artists along the way and has an entire suite of artists that I’m connected to in this mighty web of influence. That would be really exciting.

(Jeremy Harris was in convo with Nobuko Tanaka.)

––––––––––––

“Daddy” runs till July 27 at the Tokyo Globe theatre, a 6-minute walk from JR Shin Okubo station. Then it moves to Osaka and runs August 5–7 at Cool Japan Park Osaka TT Hall, a 6-minute walk from JR Osakajo Koen station. For more details, visit https://www.daddy-stage.jp