With his original interpretations of Greek dramas and Shakespeare plays staged overseas, Yukio Ninagawa, who died last year at the age of 80, was the pioneer in creating today’s worldwide following for Japanese contemporary theater.

Now, though, in 58-year-old, globe-trotting director Satoshi Miyagi, who is renowned for his groundbreaking productions of classic works, it’s clear Japan already has a worthy successor. Indeed, on July 6 in the South of France, Miyagi achieved something no Japanese had ever done before, when his production of “Antigone” became the first-ever work by an Asian dramatist to open the Avignon Festival, which started in 1947 and is one of the world’s most prestigious annual arts events.

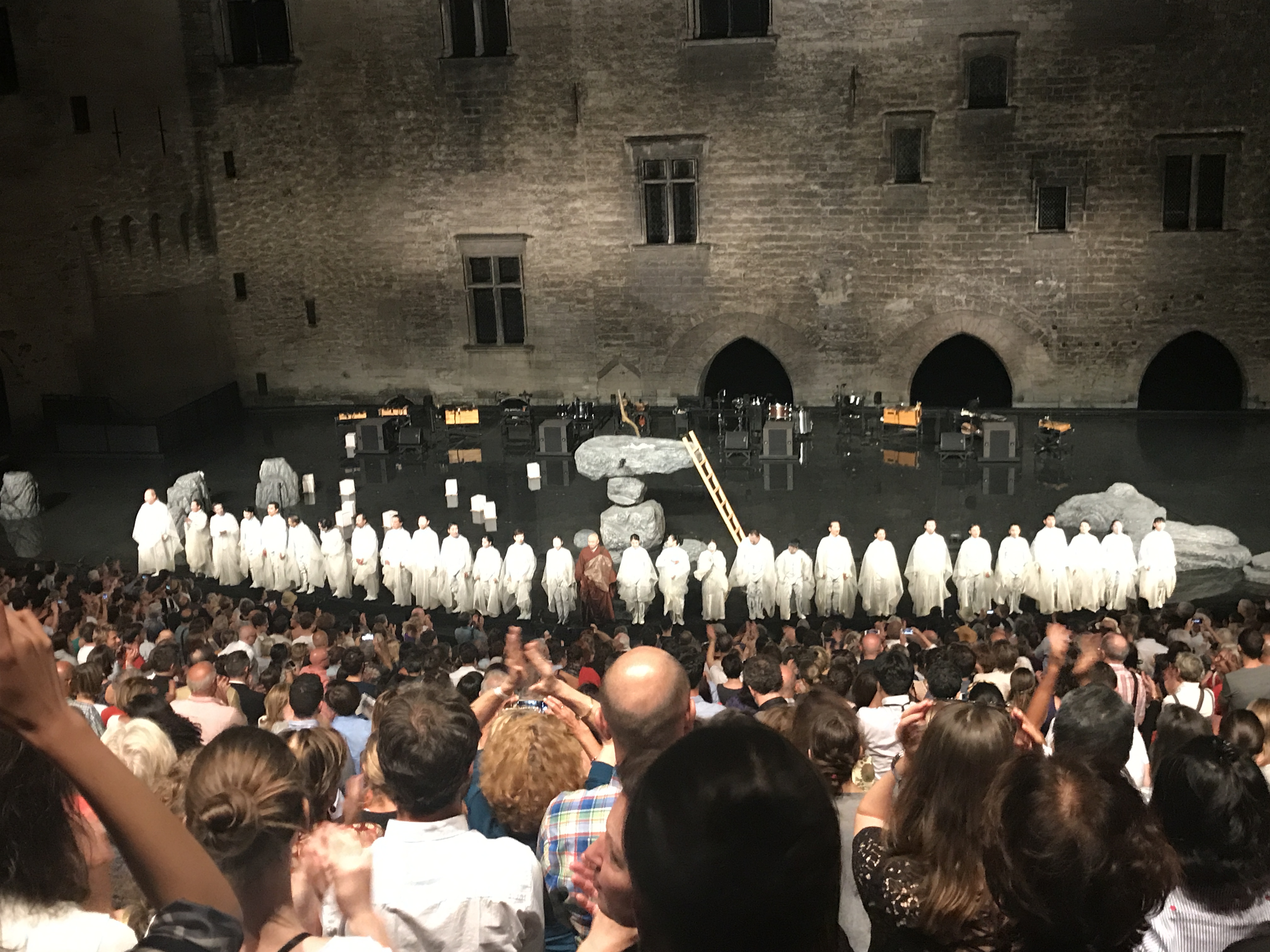

In line with Avignon tradition that goes with that great honor, Miyagi’s actors from SPAC (Shizuoka Performing Arts Center), where he is artistic director, had to present his version of Sophocles’ great tragedy from around 440 B.C. in the open-air Honors Courtyard (Cour d’honneur) of the huge, 14th-century Papal Palace (Palais des papes) in the center of town — a roofless, 1,976-seat setting surrounded by stone walls 25 meters high.

But Miyagi didn’t just make history that night, he made a lot of people very happy, too. As this writer witnessed, the cheering audience gave his production an exceptionally long standing ovation at the end.

In his “Antigone,” expressionless actors in beautiful white kimono-style costumes moved slowly around in almost ankle-deep water covering the huge stage on which boulders were positioned and piled up resembling a Buddhist stone garden.

In the original drama, two rival warrior brothers kill each other in battle, but while one of their bodies is honored the other is left out for the dogs and birds. Hence in his version Miyagi drew on death-related metaphors such as Bon festival dancing and sprit boats with candles launched on the pool — not as oriental gimmicks, but as new ways of seeing this ancient play through the prism of Japanese culture.

But if this was alien to Europeans, why were audiences reportedly so moved on every night of the July 6–12 run?

I think the answer lies in a book by Ninagawa in which he cast doubt on the universality of theater, insisting it only happens where and when it’s performed live, so a piece doesn’t need to have a global, multi-cultural approach.

From this it follows that each work is born of its creator’s cultural background — so in “Ninagawa Macbeth” the original becomes the story of a samurai commander named Macbeth presented on a stage made to look like a giant butsudan (household Buddhist altar).

I believe it’s these kinds of originality that are key to transforming Western plays into special original works by Japanese artists.