It’s been a long, long wait, but the curtain finally rose on the first Japanese version of the worldwide megahit “Billy Elliot the Musical” at the Akasaka ACT Theater in Tokyo on July 19, where it plays until Oct. 1 before moving to Osaka through Nov. 4.

In fact it’s more than 12 years since the show created by screenwriter Lee Hall and singer/songwriter Elton John, with Stephen Daldry directing, had its premiere in London’s West End — where it won four Olivier Awards and ran for 11 years before closing in April 2016 after 4,600 performances featuring a wealth of standout songs such as “Solidarity,” “Electricity,” “The Stars Look Down,” “Born to Boogie” and “Shine.”

Based on the British dance-drama film “Billy Elliot” that Daldry directed in 2000, with Hall as the screenwriter, the musical has since been staged in Brazil, Estonia, Israel, Australia, the United States and many other countries, and this production is the second with an Asian cast following one in Seoul in 2010.

Wherever it is performed, though, the original London team always works alongside local producing companies — here, that’s the giant Horipro Corp. — to ensure an authentic, top-quality show is created in each location.

In Tokyo, that process began in Nov. 2015 with an advert for applicants to play the role of Billy, a young boy from a poor, single-parent family in a dying northern English coal-mining town who dreams of being a ballet dancer. Astonishingly, 1,346 youngsters responded.

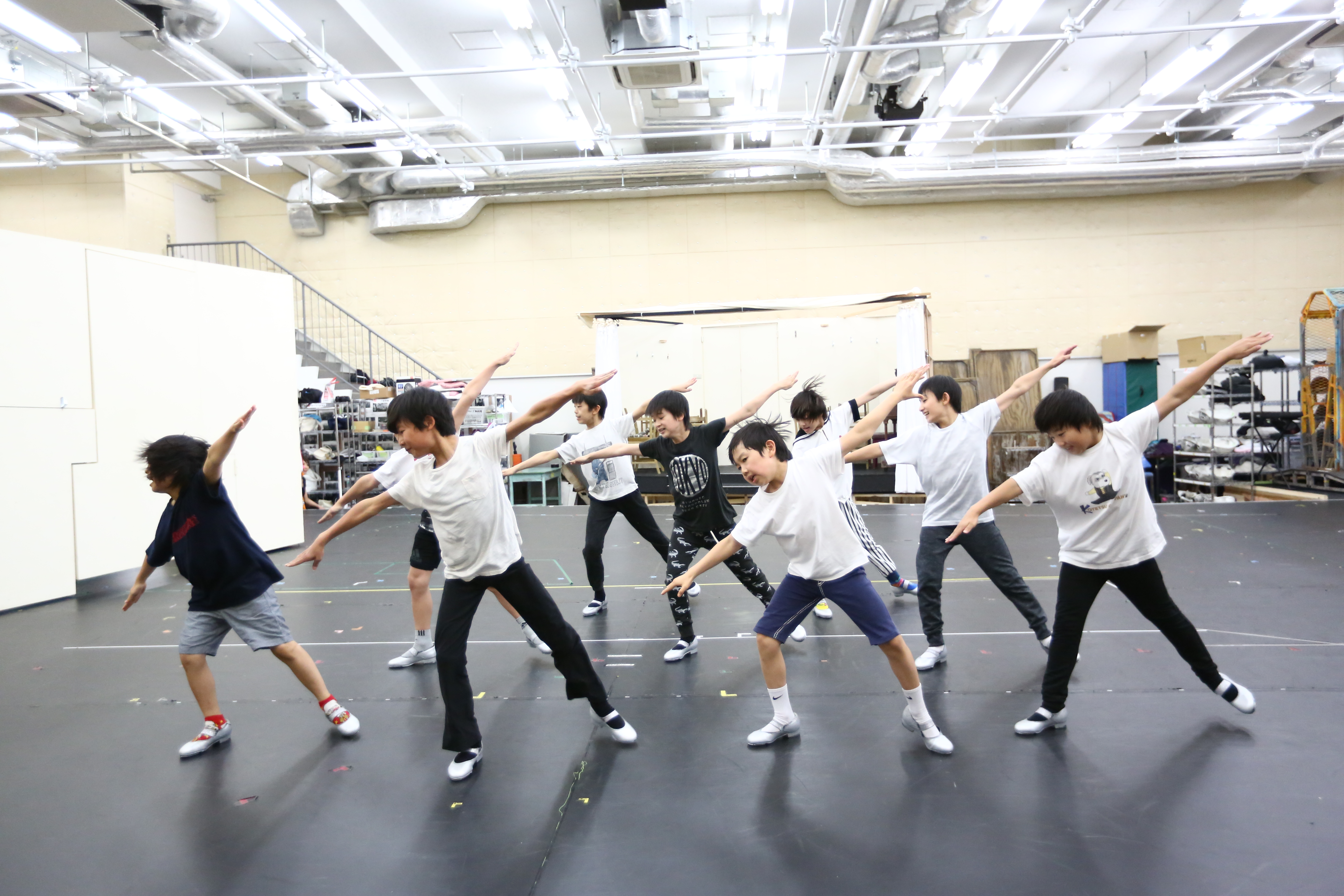

From that deluge, the production team invited 450 boys to three selective auditions in dancing held in April 2016. Within a few weeks, just 10 ho

pefuls were left to face a rigorous course of lessons in ballet, acrobatics, tap and jazz dance — and two more auditions.

Finally, on Dec. 18, four boys were named to play Billy throughout the run: 13-year-old Kousei Kato, who is already a prize-winning ballet dancer; Sakuya Kimura, 10, who was invited to audition along with his (unsuccessful) older brother; Kazuki Mirai, 14, a singer and dancer from Kumamoto in Kyushu; and Haruto Maeda, 12, a hip-hop dancer brought up in the United States.

In fact when those four were presented at a press conference back then, Maeda admitted that — whether he won through or not — he’d applied because, “I hoped I might receive top-level dance lessons in different styles.”

Sitting beside him, the youngest winner, Kimura, buoyantly declared, “I enjoyed the whole procedure … and I’ve actually met the others for longer than most of my school friends.”

Kato, too, was beaming as he told reporters about a “fun episode” when he was once told off because he started tap-dancing without realizing it during the morning meeting at school. In contrast, Mirai said, “In Kumamoto, I used to see mountains around me and I felt calm. Here, I can only see high-rise buildings, so I think how the blue sky in Tokyo is the same color as Kumamoto’s sky.”

But something’s wrong, you may think — because there are five boys in the accompanying picture. So, who is the fifth one? Well, that’s 11-year-old karate fanatic Riki Yamashiro, who’d had to swallow his tears when he was left out in December.

In fact Yamashiro’s name wasn’t added to the list until May, when Horipro’s website suddenly surprised everyone by announcing that the production team had always “had a hunch about his potential and been impressed by his positive attitude, so since December he’s been allowed to take more lessons with the other four Billys.” As a result, he’d finally landed the part.

Regarding that final fivesome, Simon Pollard, an associate director and key caster seconded from the show’s London base, disclosed in an interview with The Japan Times, “I’m excited that they’re entirely different both on the stage and off it. Consequently, each show will be different because they’ll each bring their own unique strengths to the role of Billy.”

Explaining about the selection process, he said the first criterion was some experience of dance or even of martial arts. “Then through the auditions you start to see how quickly they learn and retain information, whether their body is lithe enough for ballet but with the muscularity to handle acrobatics, and whether they have the rhythm to do tap.

“And you don’t even find many adult actors who are proficient in all those areas,” he added.

He also pointed out that it takes a while to discover each boy’s real personality — and that is key. “We chat to them and observe how they interact with each other,” he said. “Eventually they get comfortable with us and that’s when we start to see whether they have the personality to be Billy.

“In the end, I look for a boy with physical, emotional and mental strength, because this is a tough, 2½-hour show and it’s a tough part to play. We need to know they have the stamina and determination to deal with that.”

For the selected few, there awaits the role of 11-year-old Billy whose mother has died, leaving him living with his grandmother and his dad and older brother. Both the men are coal miners spending their days picketing during the bitter 1984–85 strike against government plans to close most of Britain’s pits.

In that macho male culture, Billy’s father (double cast between Kotaro Yoshida and Toru Masuoka) sends him to boxing lessons to “make him a man.” However, after watching a girls’ ballet class in the next-door room, Billy secretly switches to that and the teacher (Reon Yuzuki and Kaho Shimada) soon spots his special talent and urges him to audition for the Royal Ballet School in London.

Billy’s father is furious when he hears his son is doing “girly” ballet lessons. Then one day he sees his son dancing alone beautifully as if he’s transported, and he’s so moved he decides to support his dream of becoming a dancer. Pointedly, though, this means he has to choose between staying on strike or “turning traitor” and going back to work to pay for Billy’s trip to the London audition.

Without giving away any more of the story, Pollard said, “We often say ‘Billy Elliot’ is not a conventional musical, but a piece of political theater with great songs. The theme, though, is about a community and a family, and I think audiences here will really engage with that as others around the world have done.

“In addition,” he continued, “it’s wonderful to witness how little Billy develops as a person during the show, and how others’ relationships with him change. In fact I think being able to see the human drama in actual people’s performances is one of theater’s great qualities.”

Meanwhile, during one of the boys’ lessons I talked with their ballet teacher, Fuzuki Isaka, a principal soloist with Japan’s leading ballet troupe, K-Ballet Company. “In the future I suppose this musical will be staged again and again in Japan,” he said, “so these first cast members are crucial because kids who come to see this show, or who watch the DVD, will be hugely affected and may want to be like them some day.

“It was like that in 1999 when Tetsuya Kumakawa (the founder of K-Ballet) returned from England, where he’d been a principal at the Royal Ballet. Back then lots of Japanese boys started thinking it was cool and stylish to be a ballet dancer.”

And now, in the last few weeks, TV news has shown Amir Shah, the 15-year-old son of a welder in Mumbai who has only done ballet for two years — but has been awarded a place at the school of the top-level American Ballet Theatre in New York.

With this, and the wonderful, inspiring “Billy Elliot” musical that’s finally reached these shores, who knows how many more youngsters are out there with similar dreams set to be ignited.

For more details: visit www.BillyJapan.com